In 1965, New York City’s coffee houses were more than just places to grab a drink—they were cultural hubs where art, politics, and music collided. From Greenwich Village to Harlem, these intimate spaces nurtured the voices of a generation, hosting legendary performances and sparking social change.

Key Takeaways

- Coffee houses in NYC 1965 were cultural incubators: They provided safe spaces for artists, writers, and activists to gather, share ideas, and challenge the status quo.

- Greenwich Village was the epicenter: Neighborhoods like the Village attracted beatniks, folk singers, and poets, making it the heart of the coffee house movement.

- Music thrived in these spaces: Emerging artists like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez got their start performing in dimly lit coffee shops with acoustic sets.

- Political activism was part of the scene: Many coffee houses hosted readings, debates, and protests related to civil rights, anti-war movements, and free speech.

- Affordable and inclusive atmosphere: For just a few cents, anyone could enjoy coffee, listen to live music, and engage in deep conversation—no cover charges or dress codes.

- Legacy lives on today: Modern coffee shops still echo the spirit of 1965, valuing community, creativity, and open dialogue.

- Unique ambiance mattered: Dim lighting, mismatched furniture, and chalkboard menus created a bohemian vibe that encouraged authenticity and connection.

📑 Table of Contents

- The Birth of a Cultural Movement: Coffee Houses NYC 1965

- Greenwich Village: The Heartbeat of the Coffee House Scene

- Music, Poetry, and Performance: The Art of the Coffee House

- Politics, Protest, and the Power of Conversation

- The Atmosphere: More Than Just Coffee

- Legacy and Influence: How 1965 Shaped Modern Coffee Culture

- Conclusion: A Cup of Change

The Birth of a Cultural Movement: Coffee Houses NYC 1965

In the mid-1960s, New York City was a city in flux. The postwar boom had given way to social unrest, cultural experimentation, and a growing desire for authenticity. Amid this transformation, a quiet revolution was brewing—not in factories or government buildings, but in small, unassuming storefronts tucked into the corners of neighborhoods like Greenwich Village, Harlem, and the Lower East Side. These were the coffee houses of NYC 1965, and they became the unlikely epicenters of a cultural renaissance.

Unlike today’s sleek, Wi-Fi-enabled cafés, the coffee houses of 1965 were raw, intimate, and deeply human. They weren’t about speed or convenience—they were about presence. Patrons didn’t rush in and out with to-go cups. Instead, they lingered for hours, nursing a single cup of coffee while listening to poetry, debating politics, or strumming a guitar in the corner. The air was thick with the scent of dark roast, cigarette smoke, and intellectual energy. These spaces welcomed everyone—students, artists, activists, and dreamers—regardless of background or income. For many, a coffee house was the only place where they could truly be themselves.

What made coffee houses NYC 1965 so special wasn’t just the coffee—it was the community. In an era before social media and digital connection, these venues offered something rare: real, face-to-face interaction. They were places where ideas were born, friendships formed, and movements ignited. Whether you were a college student from Queens, a jazz musician from Harlem, or a beat poet from San Francisco, you could walk into a coffee house and find your tribe. It was a time when a cup of coffee wasn’t just a beverage—it was a ticket to belonging.

Greenwich Village: The Heartbeat of the Coffee House Scene

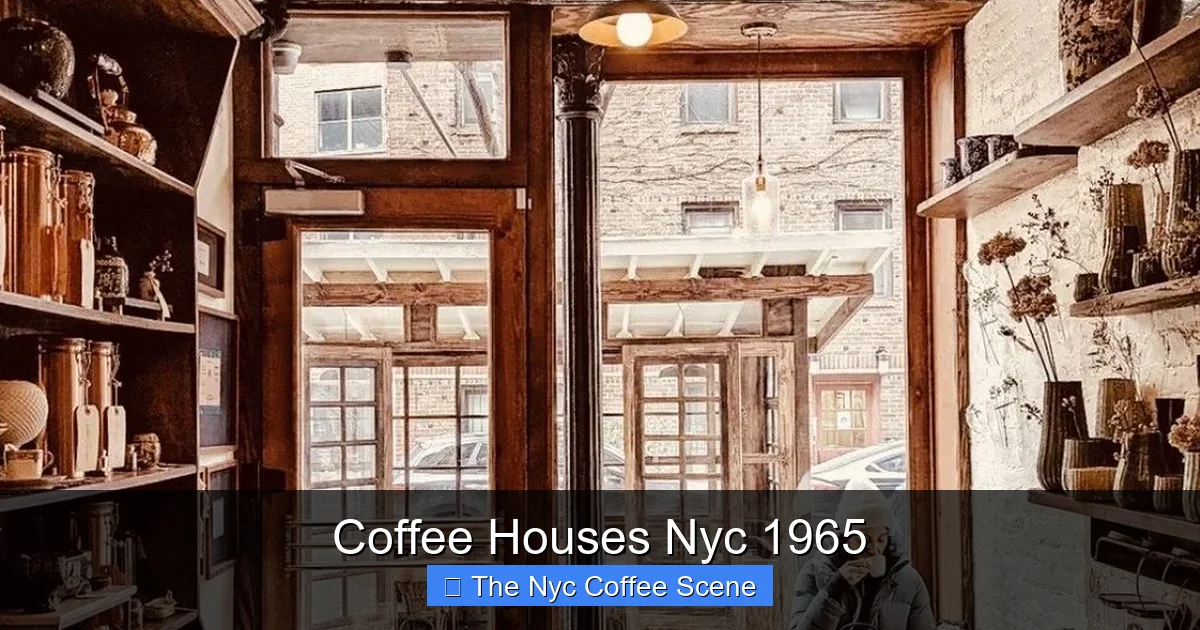

Visual guide about Coffee Houses Nyc 1965

Image source: s3-media0.fl.yelpcdn.com

If there was one neighborhood that defined the coffee house culture of 1965, it was Greenwich Village. Nestled in lower Manhattan, the Village had long been a haven for artists, radicals, and nonconformists. By the mid-1960s, it had become the undisputed capital of the coffee house movement, drawing crowds from across the city and beyond.

The Village’s charm lay in its narrow, tree-lined streets, historic brownstones, and a palpable sense of rebellion. It was a place where rules were questioned, norms were challenged, and creativity was celebrated. Coffee houses like Café Wha?, The Gaslight Café, and The Village Gate became legendary gathering spots. These weren’t just cafés—they were stages for self-expression.

At Café Wha?, located on MacDougal Street, the walls seemed to pulse with musical energy. It was here that a young Bob Dylan first performed in public, his voice raw and poetic, captivating audiences with songs that would later define a generation. The venue hosted a rotating cast of folk singers, poets, and comedians, all eager to share their work with an audience that truly listened. The atmosphere was electric—dimly lit, packed with people leaning forward in their seats, hanging on every word.

Meanwhile, The Gaslight Café, just a few blocks away, became known for its poetry readings and intimate performances. It was a place where language was as important as melody. Poets like Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti would take the stage, reciting verses that challenged societal norms and celebrated individual freedom. The Gaslight didn’t just host performances—it fostered a culture of literary rebellion.

What made these spaces so powerful was their accessibility. There were no velvet ropes or bouncers checking IDs. If you had a few cents for coffee, you could walk in, sit down, and become part of the scene. The Village’s coffee houses were democratic in the truest sense—open to all, regardless of fame or fortune. This inclusivity was key to their success. It allowed raw talent to emerge and gave voice to those who might otherwise have been ignored.

Music, Poetry, and Performance: The Art of the Coffee House

One of the defining features of coffee houses NYC 1965 was their role as performance venues. Unlike traditional nightclubs or concert halls, these spaces were informal, intimate, and deeply interactive. Artists didn’t perform *at* the audience—they performed *with* them. The line between performer and listener was often blurred, creating a sense of shared experience that was rare in mainstream entertainment.

Music was at the forefront of this cultural explosion. The folk revival was in full swing, and coffee houses were its natural home. Acoustic guitars, harmonicas, and voices filled the air, often accompanied by spontaneous jam sessions. Artists like Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, and Phil Ochs got their start in these venues, honing their craft in front of attentive, passionate crowds.

But it wasn’t just about music. Poetry readings were equally popular. The Beat Generation, though past its peak by 1965, had left a lasting influence on the coffee house scene. Poets embraced free verse, stream-of-consciousness writing, and themes of alienation, love, and social justice. At The Gaslight Café, for example, poets would often perform without microphones, their voices rising and falling with the rhythm of their words. The audience listened in rapt silence, sometimes erupting in applause or snapping their fingers in appreciation.

Performance art also found a home in these spaces. Some coffee houses hosted experimental theater, mime acts, or avant-garde comedy. The Village Gate, for instance, was known for its eclectic programming, blending jazz, spoken word, and political satire. These performances weren’t always polished—but that was part of their charm. They were raw, unfiltered, and deeply human.

What made these performances so impactful was the immediacy of the experience. There were no amplifiers, no stage lights, no recording equipment. Just a performer, an audience, and a shared moment of connection. This intimacy allowed for a level of authenticity that was hard to find elsewhere. Artists could take risks, try new material, and receive instant feedback. And audiences could engage directly—asking questions, sharing thoughts, or even joining in.

For many performers, coffee houses were stepping stones to greater fame. Bob Dylan, for example, played countless gigs in Village coffee shops before signing with Columbia Records. These early performances shaped his style and built his fanbase. But even after he achieved stardom, Dylan often returned to these spaces, reminding everyone where he came from.

Politics, Protest, and the Power of Conversation

Coffee houses NYC 1965 weren’t just about art and music—they were also hotbeds of political activism. In a time of civil rights marches, anti-Vietnam War protests, and growing distrust in government, these spaces provided a forum for dissent and dialogue. They were places where people could speak freely, challenge authority, and imagine a better world.

Many coffee houses hosted political discussions, often led by local activists or guest speakers. Topics ranged from racial equality to nuclear disarmament to student rights. These weren’t dry lectures—they were passionate, often heated debates that drew in patrons from all walks of life. A college student might argue with a factory worker; a poet might debate a union organizer. The coffee house became a microcosm of democracy in action.

The civil rights movement, in particular, found strong support in these venues. Coffee houses in Harlem and the Village often hosted benefit events for organizations like the NAACP and SNCC. Musicians would perform for free, with proceeds going to support voter registration drives or legal defense funds. Poetry readings would include works by Langston Hughes or Amiri Baraka, celebrating Black culture and demanding justice.

The anti-war movement also thrived in coffee houses. As the Vietnam War escalated, more and more young people began questioning U.S. foreign policy. Coffee houses became gathering points for draft resisters, conscientious objectors, and peace activists. Flyers for protests, teach-ins, and underground newspapers were often posted on bulletin boards. Some venues even served as safe houses for those fleeing the draft.

But perhaps the most powerful aspect of coffee house activism was its grassroots nature. Unlike formal political organizations, these spaces didn’t require membership or dues. Anyone could walk in, join a conversation, and make their voice heard. This openness made them uniquely effective at mobilizing people and spreading ideas.

Even the act of drinking coffee became political. Many coffee houses refused to serve segregated groups or supported fair labor practices. Some sourced their beans from cooperatives in Latin America, promoting economic justice alongside social change. In this way, the coffee house was more than a place to relax—it was a statement of values.

The Atmosphere: More Than Just Coffee

Walking into a coffee house in NYC 1965 was like stepping into another world. The ambiance was carefully crafted to encourage conversation, creativity, and contemplation. Every detail—from the lighting to the furniture to the menu—was designed to foster a sense of community and authenticity.

Lighting was soft and warm, often provided by dim lamps or string lights. Candles flickered on tables, casting long shadows on brick walls. This intimate glow made people feel safe and relaxed, encouraging them to open up and share their thoughts. It was the opposite of the bright, fluorescent lighting found in diners or offices.

Furniture was typically mismatched and slightly worn—wooden tables, wicker chairs, and couches with faded upholstery. This lack of uniformity gave the space a lived-in, bohemian feel. It wasn’t about luxury; it was about comfort and character. Patrons often rearranged the furniture to suit their needs, creating small circles for conversation or clearing space for a performance.

The menu was simple but intentional. Coffee was the star—usually brewed strong and dark, served in thick ceramic mugs. Tea, hot chocolate, and pastries were also available, but the focus was on the experience, not the food. Prices were low, often just 25 cents for a cup of coffee, making it accessible to students, artists, and low-income patrons.

Music played a subtle but important role in setting the mood. Jazz records spun on turntables in the background—Miles Davis, John Coltrane, or Thelonious Monk. The music wasn’t loud; it was meant to enhance the atmosphere, not dominate it. It provided a soundtrack for conversation and reflection.

Perhaps the most important element of the atmosphere was the lack of pretension. There were no dress codes, no cover charges, no VIP sections. Everyone was treated equally. A famous poet might sit next to a construction worker, and neither would think twice about it. This egalitarian spirit was central to the coffee house ethos.

Legacy and Influence: How 1965 Shaped Modern Coffee Culture

Though the heyday of coffee houses NYC 1965 has long passed, their legacy lives on in today’s coffee culture. Many of the values and practices that defined those spaces—community, creativity, inclusivity—can still be found in independent cafés across the city and beyond.

Modern coffee shops often strive to recreate the intimate, human-centered atmosphere of the 1960s. They host open mic nights, poetry readings, and art exhibits. They prioritize local sourcing, fair trade, and sustainable practices—echoing the social consciousness of the era. And they remain spaces where people gather not just to work or study, but to connect.

The rise of the “third place” concept—a space between home and work where people can relax and socialize—owes much to the coffee houses of 1965. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term decades later, but he was describing something that already existed in the Village and beyond.

Even the language of coffee culture has roots in this period. Terms like “bohemian,” “beat,” and “folk revival” are still used to describe certain types of cafés and their clientele. The idea that a coffee shop can be a cultural hub, not just a retail outlet, is a direct descendant of the 1965 model.

Of course, today’s coffee scene is different in many ways. Technology has changed how we interact, and commercialization has altered the landscape. But the spirit of the coffee house—the belief that a cup of coffee can be a catalyst for connection and change—remains powerful.

For anyone interested in the history of New York City, the coffee houses of 1965 offer a fascinating window into a transformative era. They remind us that culture isn’t just created in studios or theaters—it’s born in the everyday spaces where people come together.

Conclusion: A Cup of Change

Coffee houses NYC 1965 were more than just places to drink coffee. They were sanctuaries of expression, hubs of activism, and stages for artistic discovery. In a city known for its pace and pressure, these spaces offered something rare: time to think, to talk, to create.

They proved that culture doesn’t need grand stages or big budgets to thrive. Sometimes, all it needs is a quiet room, a warm cup, and a group of people willing to listen. The legacy of those coffee houses continues to inspire, reminding us that the simplest spaces can hold the most powerful ideas.

So the next time you sip your latte in a cozy corner café, take a moment to appreciate the history behind it. You might just be sitting in the spiritual descendant of a 1965 coffee house—where a revolution once brewed, one cup at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What made coffee houses in NYC 1965 different from today’s cafés?

Coffee houses in 1965 were cultural and political hubs, not just places to grab a drink. They emphasized community, live performance, and open dialogue, with minimal focus on speed or convenience.

Which neighborhoods were known for their coffee house scenes in 1965?

Greenwich Village was the epicenter, but Harlem and the Lower East Side also had vibrant coffee house cultures, each with its own flavor and community focus.

Did famous musicians perform in coffee houses in 1965?

Yes—artists like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Pete Seeger got their start performing in intimate coffee house settings, often for little or no pay.

Were coffee houses in 1965 politically active?

Absolutely. Many hosted discussions, protests, and benefit events related to civil rights, anti-war movements, and free speech, making them key sites of activism.

How much did a cup of coffee cost in 1965?

A typical cup of coffee cost around 25 cents, making it affordable for students, artists, and low-income patrons.

Do modern coffee shops still reflect the spirit of 1965 coffee houses?

Many do—especially independent cafés that host live music, poetry, and community events, continuing the tradition of fostering connection and creativity.